Little Italy and the Quarries Along the Potomac

During the first decade of the 20th century, an influx of Italian and Sicilian immigrants occurred to provide laborers for the Potomac River quarries.

In 1833, a group of Washington businessmen, including William Corcoran, bought land along the Potomac, formerly belonging to John Mason. The land was subdivided in 1835 to include forty-three quarry lots between Three Sisters Island and Pimmit Run. Corcoran sold these lots to William Easby in 1845 and remained in Easby's ownership until 1890 when his heirs sold the property. The quarries continued operating into the twentieth century, and one of the later owners was the Columbia Granite and Dredging Company.

In 1851, Gilbert Vandewerken bought land along the Potomac and set up quarries following the Civil War to take advantage of the post-war construction boom in Washington. He operated three quarries: one below Chain Bridge, one at Gulf Branch, and one below Spout Run. These quarries were also used in the twentieth century under various ownership, and one of the companies included the aforementioned Columbia Granite and Dredging Company.

Throughout the history of these quarries, rock was blasted, hammered, and drilled from the cliff faces. In the early years, most work was done by hand. As the years wore on, mechanized equipment was employed, but much manual labor was still involved. Gilbert Vanderwerken's grandson described how men would use a steam-powered drill hammer to create a hole in the rock for blasting powder. Once the rock was blasted, the resultant rubble and the larger building stones were hauled by the men in wheelbarrows to waiting scows on the river. Evidence of the quarry operations is preserved along the Potomac shoreline in the form of rusting hulks of equipment, including boilers to power steam-driven tools and concrete bunkers for storing dynamite. Period maps also indicate quarry-related features such as a compressor house and a boat landing.

During the first decade of the twentieth century, an influx of Italian and Sicilian immigrants occurred to provide laborers for the Potomac River quarries. As they became employed here, they could make their homes along the company lands in exchange for modest rentals. A scattering of shacks soon dotted the hillsides overlooking the Potomac in the area between Spout Run and Pimmit Run, with a concentration in the Marcey Creek ravine, and were collectively referred to as Little Italy or Little Sicily. Life in this community of quarrymen has been referred to, perhaps romantically, as "colorful, hard, and sometimes violent, resembling that of early western mining towns," complete with fights and shootings.

One family who made their residence in Little Italy was that of Michele Dimeglio, an Italian immigrant from Naples who came to the United States in 1903 as a nineteen-year-old man. He moved to this area via West Virginia, where he had worked in a quarry and married an Irish woman named Cora Woodlock. The Dimeglios eventually had ten children: Charlie, Eva, Louise, Willie, Mary, Jimmy, Eddie, Joe, Betty, and Mike. The Dimeglios had all taken Miller's Anglicized surname, following the lead of the eldest son, Charlie, to fit into American society better. Staff at the George Washington Memorial Parkway, with the assistance of NCR Ethnography program funding, had the opportunity in 2007 to conduct an oral history interview with the youngest son and daughter, Mike Miller and Betty Binns, as well as the husband of Betty, Marvin Binns, a life-long Arlington County resident.

Betty and Mike were born in 1934 and 1939, respectively, and lived in Little Italy into their teen years. Betty, Mike, and their siblings were the only children in the immediate area, and some of their older brothers and sisters had moved out, married, and begun having children when Betty and Mike were born. The children led a relatively simple life, going to public schools and playing along the Potomac River, swimming, fishing, boating, and wandering the hillsides. They spoke of jumping into the Potomac River from a rope swing atop a "40-foot rock" near Spout Run, of purchasing a treat from the ice cream scow that visited along the shoreline, and of rowing boats up and down the river.

The quarrying industry was winding down even before Betty and Mike were born, and they had no childhood memories of their father working in the quarries, only family stories. The last company that Mr. Dimeglio had worked for was Smoot Sand and Gravel, one of the previous quarry the gorge, which ceased operations in 1938. They recalled that their father received a check, likely Social Security or public assistance, food stamps, and also tended several garden plots. Their mother, Cora, stayed home to raise the children and do household chores. Betty and Mike described their house as a little: a simple four-room shack made of materials that were easily attainable and affordable, usually cheap lumber, tar paper, and corrugated tin. Most often, windows were covered with chicken wire, though some had glass. There was no electricity or running water; kerosene lamps provided light, and springs supplied water. A wood stove provided the heat.

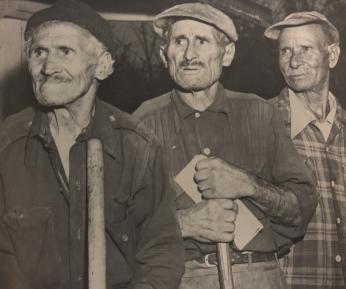

Near the Dimeglio residence, Betty and Mike recalled that there lived only a few other individuals during their youth, as most of the occupants of Little Italy had departed following the closing of the quarries. Brothers Giuseppe (Josh) Conducci and Carmelo (Carl) Conducci, Phillip (Phil) Matoli, and a couple of other individuals were the only ones remaining. Betty left Little Italy at age 17 and married, having two children with her first husband, who later died, before marrying her current husband, Marvin Binns. Mike went to live with a sister in Maryland at about the time Betty left, which was around 1951. Though they didn't indicate it, this was reportedly the year when their father died.

Josh, Carl, and Phil were the last inhabitants of Little Italy, forced to move in 1956 after the federal government acquired the land to extend the George Washington Memorial Parkway. Though the quarrying industry has disappeared from the Potomac Riverfront and the George Washington Memorial Parkway lands, remnants of this activity survive in the form of the jagged cliff faces that had been quarried and the abandoned equipment used to extract the rock from the gorge. A former quarry area is evident as one drives the Parkway near Spout Run. As one hikes the Potomac Heritage Trail along the Potomac shoreline, various pieces of equipment are encountered. These relics of the former quarrying activities remind the landscape of past lives along the Parkway.

Images