At the outbreak of the Civil War his property became of mutual interest to both Confederate and Union forces.

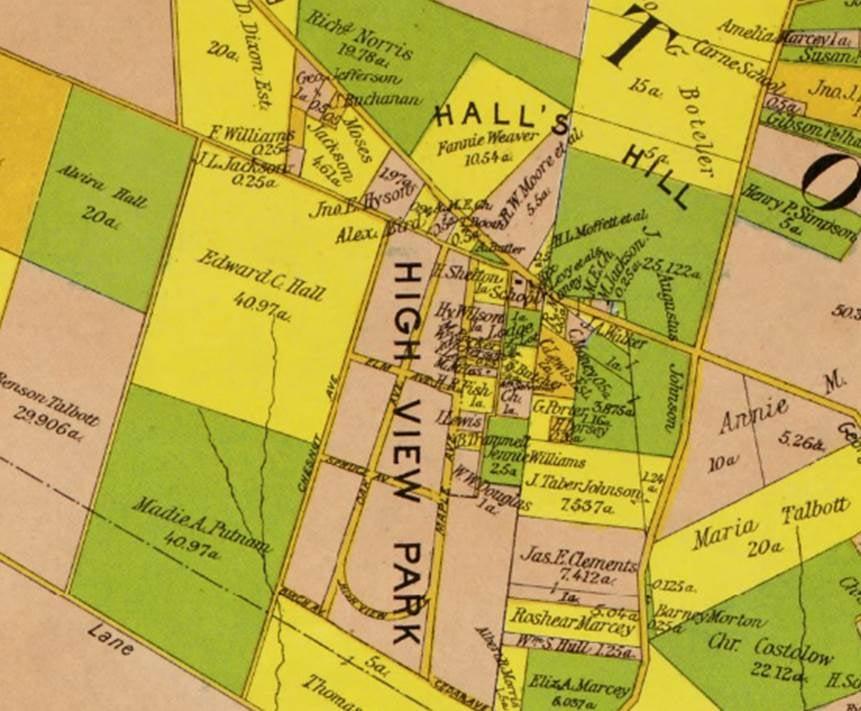

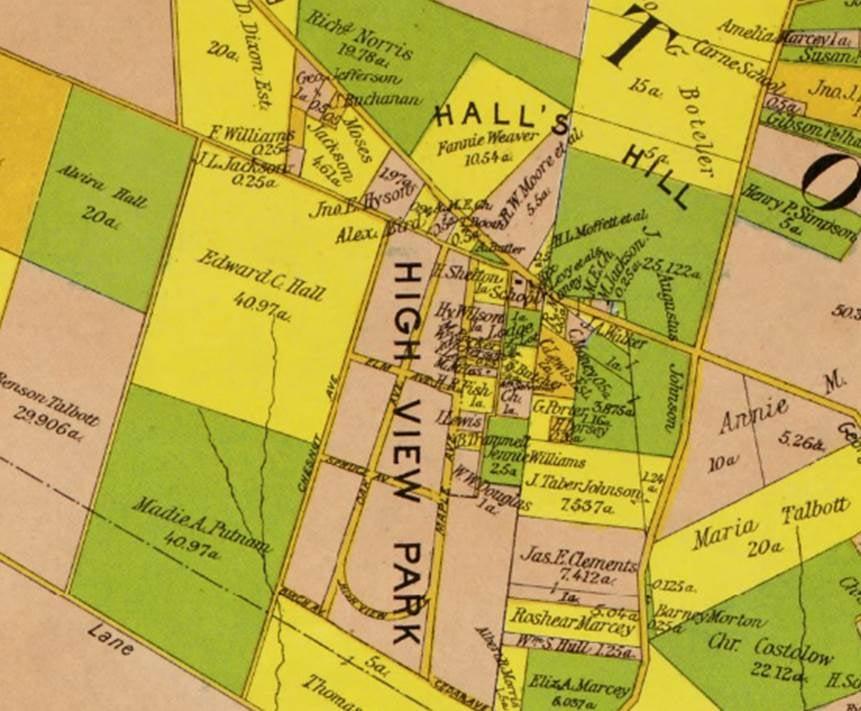

On December 13, 1852, Bazil Hall, reputedly a whaling captain (and brother to the infamous DC “businesswoman” Mary Ann Hall), bought 327 acres of land in what is now Arlington. Hall’s estate had orchards, livestock, timber, and crops such as corn. Bazil built a house, estimated to have cost $3,000, atop the 400-foot summit of his property.

Enslaved people maintained his land and house. The 1860 Slave Schedule lists Hall as owning a family of enslaved people, including Jenny Farr and her son, James Clark, as well as three additional children born into slavery on the Hall estate. Records indicate that the Halls were very harsh enslavers. The Alexandria Gazette reported Jenny ended up killing Basil’s wife, Elizabeth, in 1857.

Three years later, Hall remarried 23-year-old Frances Ann Harrison, a relation of President William Henry Harrison. In 1860, Hall's farm was valued at $10,000 and his personal effects at $15,000, or at least $235,000 and $354,000, respectively.

Although he owned enslaved people, Hall was a staunch Unionist. At the outbreak of the Civil War, his property became of mutual interest to both Confederate and Union forces, but for entirely different reasons. Confederate troops moved into what is now Arlington County in August 1861 and set fire to Hall's home in an attack launched from neighboring Upton's Hill.

When Union troops pushed into the county, they occupied Halls Hill and the adjacent hills. Camps stretched for miles, and Hall's Hill, in particular, presented Union troops with an almost unimpeded view of Washington and the surrounding area. Union occupation of Hall's Hill lasted through 1862, and the troops stripped it of all timber and fencing. They had confiscated Hall's livestock early on, most of which became food to feed troops. Hall’s property was considered an ideal site due to the abundance of timber and availability of water from a stream and wells.

A year after the Civil War ended, Hall began dividing his land among relatives, but he also sold one-acre lots to formerly enslaved people at below-market prices. He didn’t sell his former slaves' land because he was nice. His white neighbors surmised at the time that he just wanted to irritate them by having African-American neighbors. In 1870, his estate was appraised at $6,400, while his personal effects were valued at $300.00. He filed a $42,000 claim with the Southern Claims Commission for losses incurred during the war and was eventually awarded a settlement of $10,700 in June 1872.

Images