Minor's Hill

Minor’s Hill evolved from a simple cabin-style home in the early 1800s to a more expansive country estate in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It became famous as a stopover and respite for First Lady Dolley Madison during the War of 1812.

Minor's Hill summit rises 459 feet above sea level, making it the highest point in Arlington County. It is named after Colonel George Minor, who lived there during the American Revolutionary War. Minor's Hill straddles the border of Arlington and Fairfax counties, and its southern and southwestern boundaries are defined by Four Mile Run. Mount Daniel is to the west, and Upton’s Hill is to the east.

Minor’s Hill evolved from a simple cabin-style home in the early 1800s to a more expansive country estate in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It became famous as a stopover and respite for First Lady Dolley Madison during the War of 1812. She escaped the burning City of Washington, careful to take with her the most famous documents of the young country, notably original copies of the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution. She also took the famous Gilbert Stuart painting of President George Washington, which hung in the White House. The large wooden frame of the painting had to be unbolted from the White House wall, and then the canvas of the artwork itself was cut from the frame, rolled up, and stored in a tube for transport, all while the British soldiers were just a short distance away and the City under attack.

After assuring the safe packing of the documents and the portrait, she left the White House, first making her way west to Bellevue, now known as the Dumbarton House. This large Federal-style mansion on Q St. in Georgetown was completed around 1800. Dolley waited there for her husband, President James Madison. She received word that his plans had changed, and he would not be able to join her there in the relative safety of Georgetown but that she should leave and go to the other side of the Potomac, where they would meet.

After a failed attempt to rendezvous at the Georgetown Ferry, the First Lady and her group traveled west along the north bank of the Potomac (today’s Canal Road) to the Chain Bridge near the Little Falls of the Potomac. There, she crossed over into Virginia. She traveled up the steep Falls Road (now Chain Bridge Road) on foot, then turned off for Rokeby, a large mansion further north and west towards Leesburg. There, the group spent the night of August 24, 1814. Even from a distance of 20 miles or more, the flames from the burning city of Washington were visible. Rokeby thus became known as a “repository for U.S. Government documents.” The Declaration of Independence was reputedly hidden in the basement.

The following morning, the group left Rokeby for Salona, another estate plantation in present-day McLean, Virginia. The next day, with paintings and documents, Dolley left her husband and traveled further inland to Wiley’s Tavern on the Alexandria and Leesburg Road (today’s Leesburg Pike), where she spent the next night. On August 26, 1814, Dolley and her group returned to the still-burning capital city. She stayed at the estate on Minor's Hill for two nights before leaving on August 28th to return to the ruins of Washington City. The President's House had been destroyed by fire, so she continued to the home of her sister Anna and her husband, former Congressman Richard Cutts, who had survived on F Street.

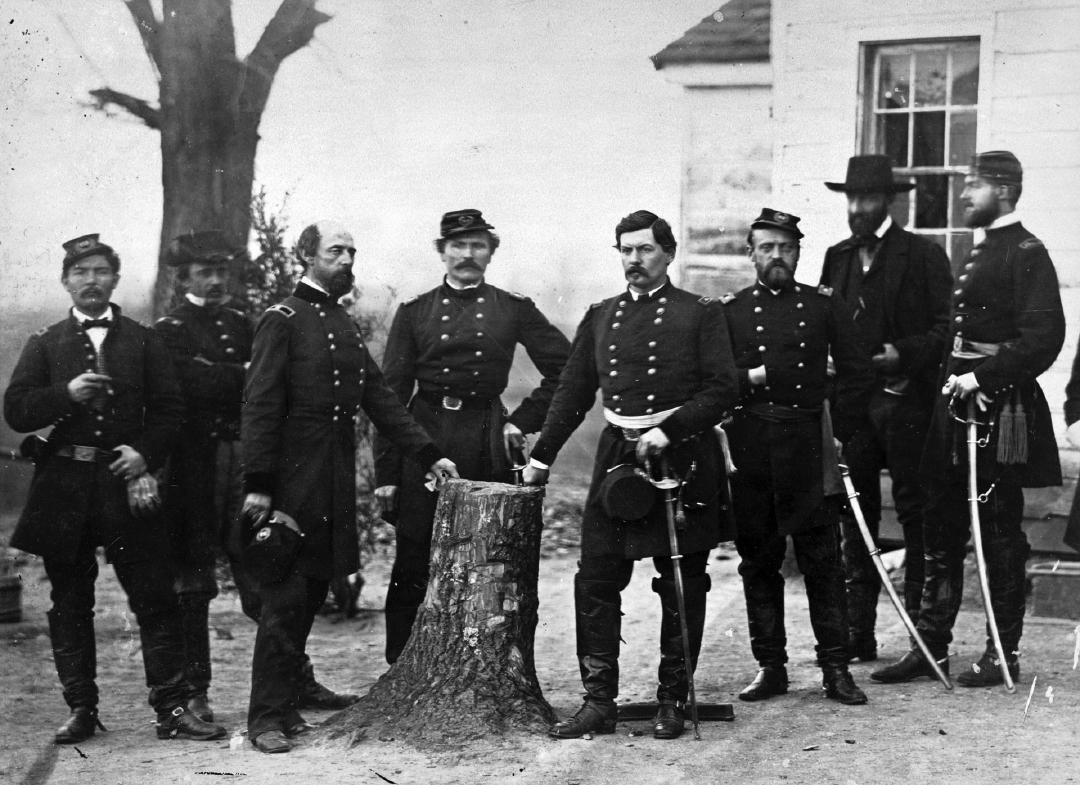

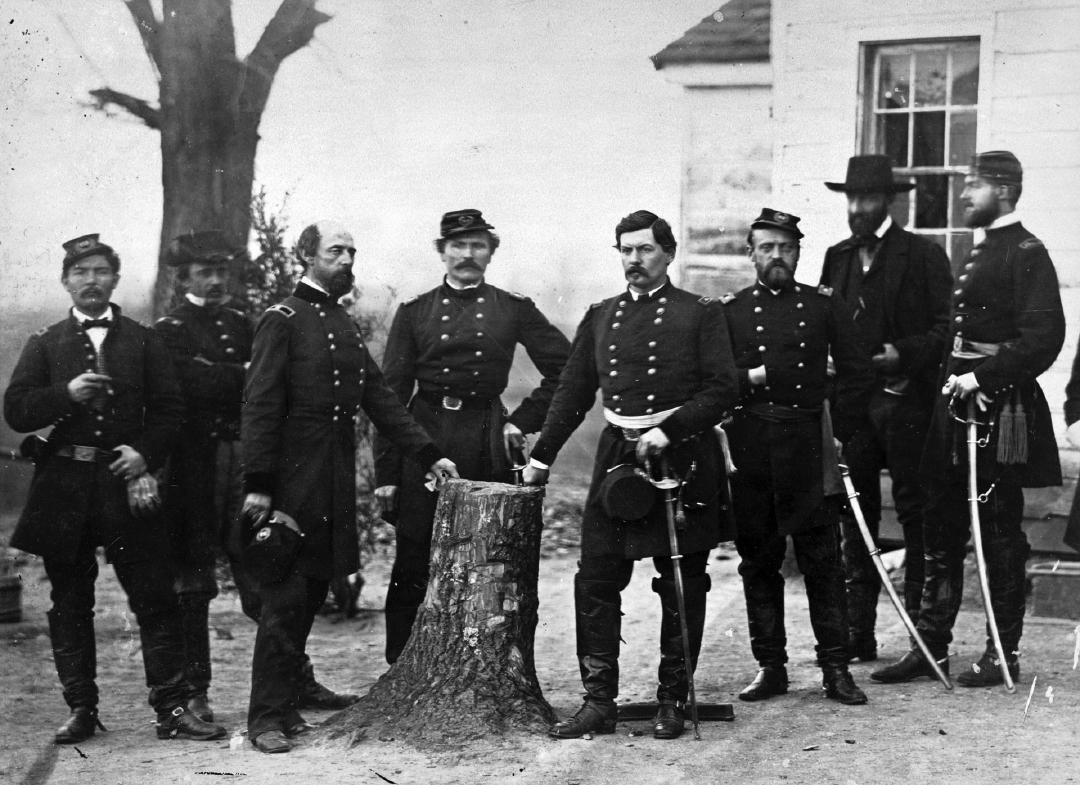

Minor's Hill had another run-in with history during the Civil War when it was used as a signal station and an observation post to protect Washington from Confederate forces. General McClellan, among other well-known Civil War figures, was photographed in front of the Minor home in March 1862. Union soldiers sometimes referred to it as Minor Hill and Minors’ Hill, and it often appeared in newspaper accounts and soldiers’ letters as “Miner’s Hill.”

The Minor family were secessionists and supported Virginia's bid to leave the Union—and clandestinely supported the Confederate Army and its movements throughout the war. At the beginning of the war, Colonel Minor, who was said to be 80, fled his home for the safety of Virginia's interior. When Union troops occupied it, they found his War of 1812 orders, signed by Secretary of State James Monroe, directing him to the defenses of Washington at Bladensburg. It was a document "he certainly must prize," as one report put it.

During the Civil War, Confederate raids from Falls Church extended as far east as Balls' Cross Roads, now known as Ballston. The area surrounding the base of the hill was the site of several skirmishes. However, in September of 1862, the Union Army experienced a second devastating loss in battle at Manassas, which forced them to retreat and pull their forces towards Washington to protect the capital. Seven Union regiments encamped on Minor's Hill, establishing Camp Barnard, Camp Bettie Black, Camp Burnham, Camp Cameron, Camp Carl Schurz, Camp Cromwell, and Camp Owen, among several smaller encampments.

Following the Civil War and until the 1940s, the hill remained rural. During the 1950s, urbanization spread west from Washington, and by the 1960s, the entire hill was developed for housing. A public park on Williamsburg Boulevard at Powhatan Street commemorates the hill's name and helps preserve it as a place name. The Minor house was torn down in 2016.

Images