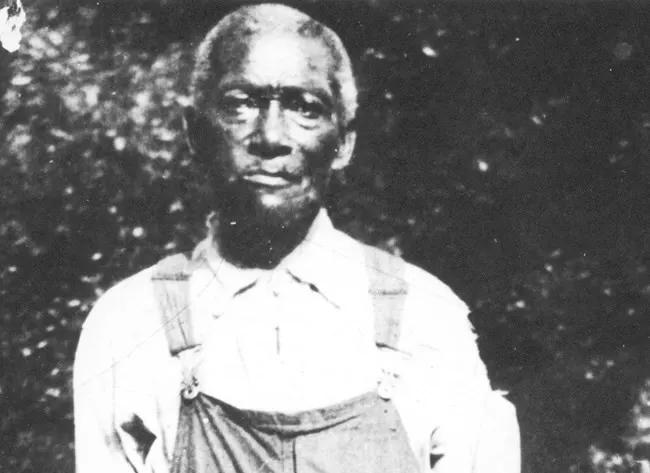

James Parks

Arlington House was not only home to the Custis-Lee family but also to sixty-three enslaved people who lived and worked there. Among those enslaved individuals was James Parks, also known as Jim Parks. Without him, the story of Arlington would not be complete.

Arlington House was not only home to the Custis-Lee family but also to sixty-three enslaved people who lived and worked there. Among those enslaved individuals was James Parks, also known as Jim Parks. Without him, the story of Arlington would not be complete.

James Parks was born sometime in 1843 to Lawrence Parks and Patsy Clark. As an enslaved person working in the field, Mr. Parks rarely saw the mansion inside, but he did remember what happened outside the house. He recalled George Washington Parke Custis, the owner of Arlington, playing the fiddle for dances held in the pavilion near the river. He remembered little about Robert E. Lee, Mr. Custis' son-in-law, but he could name the Lee children from youngest to oldest.

James Parks also had vivid memories of the deaths of Mr. and Mrs. Custis. Of Molly Custis, he stated that she died "four years before Major Custis went, too." Lawrence Parks, the father of James Parks, was one of the pallbearers for Mrs. Custis's funeral. Present at the burial of Mr. Custis in 1857, James Parks remarked on the division of the races: "We were standing with the other black folks apart from the white folks, when they laid Mr. Custis beneath his trees not far from the great house that stands today overlooking the Capital City," quoted from the 1928 Sunday Star article written about James Parks.

James Parks was eighteen years old at the beginning of the Civil War. By May of 1861, the Lees had moved to Richmond, Virginia, leaving the enslaved people and an overseer at Arlington. This was when people believed that the bloodshed from the war would fit in a lady's thimble. James Parks witnessed the aftermath of the battle that would change everyone's minds. He saw Union soldiers streaming over the old road near the present location of the US Marine Corps War Memorial, running towards Washington after the first battle of Manassas. Following that defeat, the Union army entrenched itself on the grounds of Arlington, building fortifications. James Parks helped construct Fort McPherson and Whipple, Fort Myer today.

In 1864, two hundred acres of the Arlington estate were set aside as a cemetery for the dead from the Civil War. James Parks stopped building forts and began digging graves. In 1929, he showed the Sunday Star reporter where "coffins had been piled in long rows like cordwood." He eventually prepared the grave of Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs, who was responsible for converting Arlington into a cemetery.

James Parks married twice and fathered twenty-two children. He continued to work at Arlington Cemetery until 1925. That year, Congress voted to restore the mansion to its 1861 appearance, the last year the Lees had lived on the estate. The mansion's interior was restored partly from the accounts of some enslaved people who worked in the house and partly from the 1853 Lossing article published in Harper's New Monthly Magazine. The exterior was neglected until 1928 when James Parks gave his account of the plantation layout to Lieutenant Colonel G. Mortimer, quartermaster for the Marine Corps.

James Parks provided specific locations for the wells, springs, enslaved quarters, cemeteries, dance pavilions, old roads, icehouses, blacksmith shops, and kitchens. Mr. Parks stated that all of his grandparents and parents were buried in the slave cemetery. At the time the article was written, the Department of Agriculture was in the process of uprooting the sacred ground for a farming area. It is not known what happened to the bodies interred in the enslaved cemetery.

When James Parks died in August of 1929, he left behind one of the few published accounts from an enslaved person from which Arlington House was restored. His testimony provides a more complete record of the people who inhabited the plantation: the enslaved people and the Custis-Lee family. The only person buried in Arlington Cemetery born on the old plantation, James Parks, was laid to rest with full military honors: a fitting tribute to a man whose life linked Arlington's past and present.

Images