Crepe Upon the Doors: Epidemics in Arlington County

In 1918, Arlingtonians confronted the deadly Spanish Influenza pandemic.

Battling the coronavirus, the government asked Arlingtonians to shut down businesses, cultural facilities, and schools while requesting residents stay home to stop the spread of the highly contagious pathogen.

Epidemics swept through America and Arlington in the past. In 1918, Arlingtonians confronted the deadly Spanish Influenza pandemic. How they responded to this public health emergency shaped how they would react to future crises. Let’s take a look back and see how they coped with its devastating impact.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, before public health was regularly practiced, outbreaks of typhoid, smallpox, diphtheria, scarlet fever, and cholera were common in Arlington (called Alexandria County until 1920). Lack of rudimentary sanitation caused most of the surges in disease.

In 1918, the Spanish Flu epidemic, the worst pandemic in American history, erupted. The Spanish Flu probably originated in Kansas. It quickly spread worldwide as US troops traveled to Europe to fight in World War I. About 500 million people around the globe became infected. The number of deaths reached roughly 40- 50 million, with about 675,000 occurring in the United States.

The flu first appeared in the winter of 1918, but the second wave of the pandemic, beginning in the fall of 1918, was much deadlier. The first wave attacked the sick and elderly, while younger, healthier people recovered quickly. By the second wave, the virus had mutated into a more virulent form, taking young and old alike. In Arlington and beyond, October 1918 was the most destructive month of the whole pandemic.

The US Public Health Service, the Virginia State Board of Health, and the Executive Committee of the Virginia Council of Defense acted to limit the transmission of the virus by posting notices in newspapers and public spaces. By appealing to the patriotism of Virginians, state officials convinced residents to remain at home and avoid gatherings.

The Spanish Influenza caused high fever, sore throat, a cough, and sometimes a severe nosebleed. It was highly contagious.

Preventing the spread of the Influenza saved lives. Health experts advised citizens to avoid crowds and common drinking cups and to cover one’s mouth when coughing. Less conventional suggestions included, “Don’t put into your mouth fingers, pencils or other things that don’t belong there” and not “to expectorate promiscuously.” In the Washington Post, authorities warned readers “against gorging at dinner time” and ”above all things,” to “try to stay cheerful.”

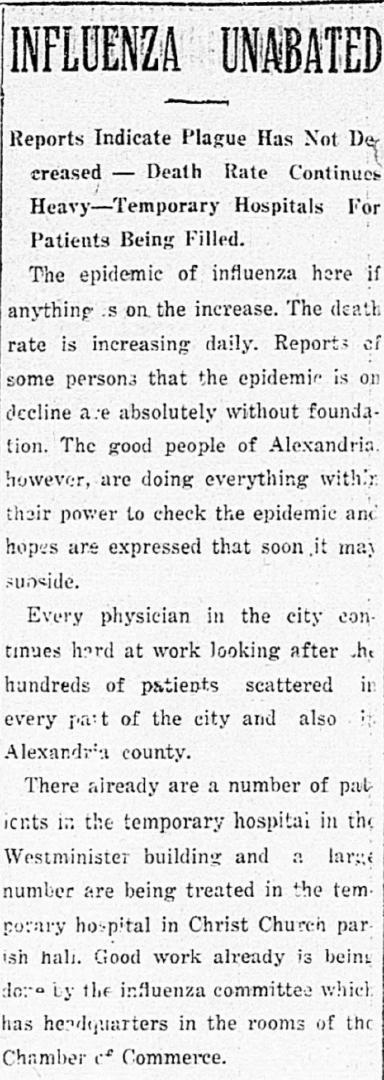

In Arlington and beyond, schools, theaters, churches, and many stores closed to help contain the virus. Unable to find healthy jurors, the court system was also essentially shut down.

The Influenza epidemic ravaged Arlington and Alexandria City, as well as large pockets of Virginia. Health officials scrambled to find additional nurses and doctors and to create temporary hospitals for the overflow of patients. In Richmond, authorities cut corners by allowing medical students to work as physicians. In the end, 54 Arlingtonians died from the Spanish Flu and uncounted were sickened.

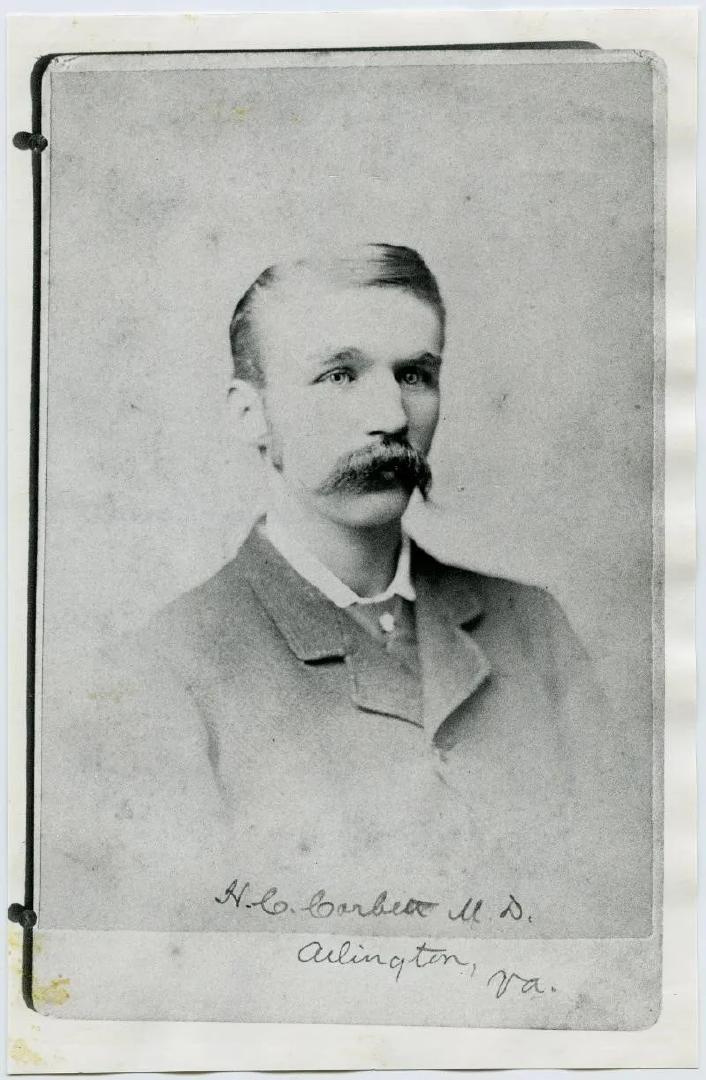

Dr. Henry C. Corbett, the Secretary of the Board of Health for Arlington and the “pioneer” of health services in Arlington, oversaw the crisis in the county. He visited hundreds of patients a day, dispensing a concocted treatment of atropine capsules (belladonna) and whiskey.

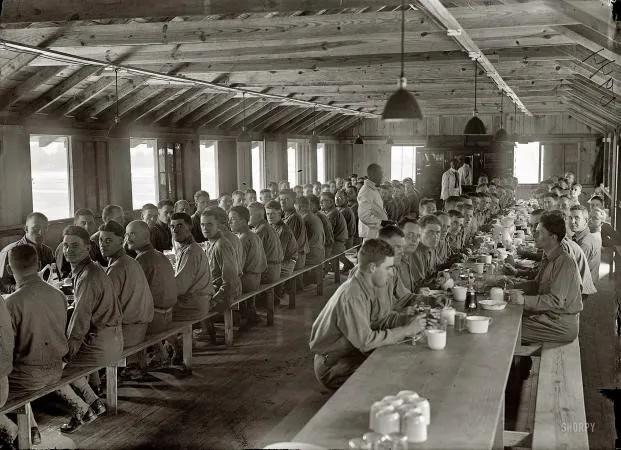

Soldiers stationed at Fort Myer, the US Army post by Arlington National Cemetery, were especially vulnerable to the Spanish Flu. Infections spread quickly amongst those in close quarters. Recruits ate in communal mess halls and lived in tightly packed barracks.

Fighting the Spanish Flu changed Arlingtonians’ perception of the importance of public health. It probably influenced the decision, in 1919, to establish Arlington’s first Department of Health and to hire Dr. JW Cox to lead it. The agency sought to improve sanitation throughout the county in hopes of preventing, not just reacting to, the spread of disease.

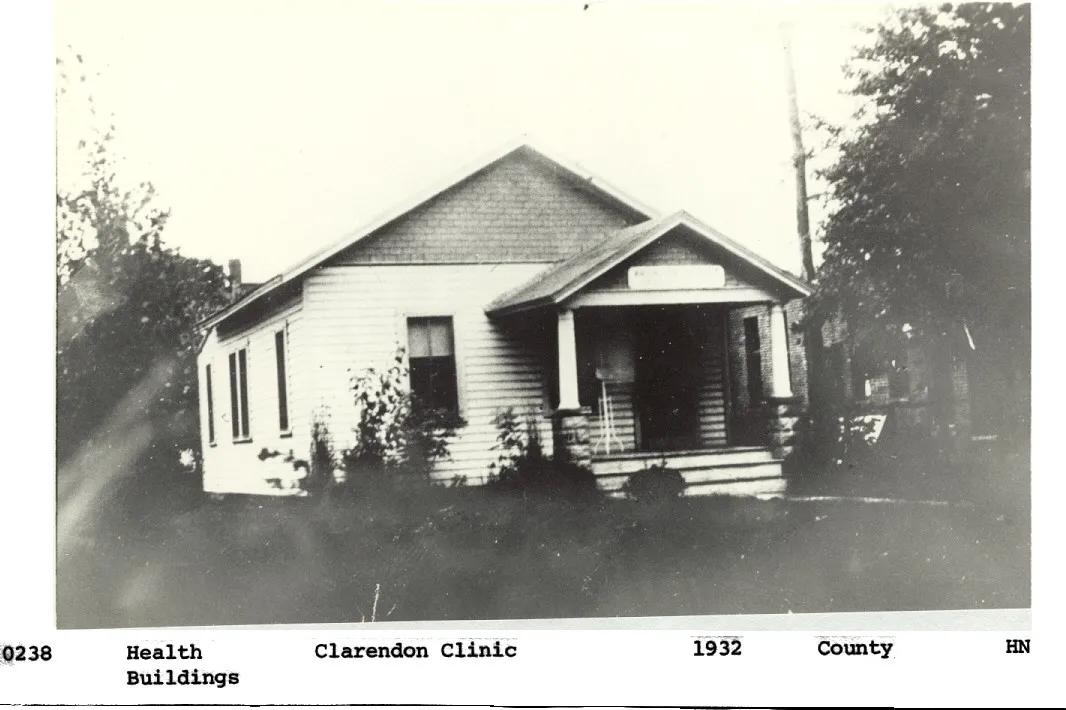

Beginning in 1921, Arlington opened clinics in each of its three Magisterial Districts: Arlington, Jefferson, and Washington. There was no municipal water service or sewage system in any of the Districts.

In 1924, Arlington’s Department of Health appointed Dr. Peyton M. Chichester, as its second director. He brought important health improvements to the county, including the building of water and sewer systems and instituting child health programs. Chichester also managed immunization, anti-fly, and public education campaigns to help eradicate communicable diseases. Dr. Chichester became a beloved figure in Arlington.

Images