Rediscover Grace Murray Hopper

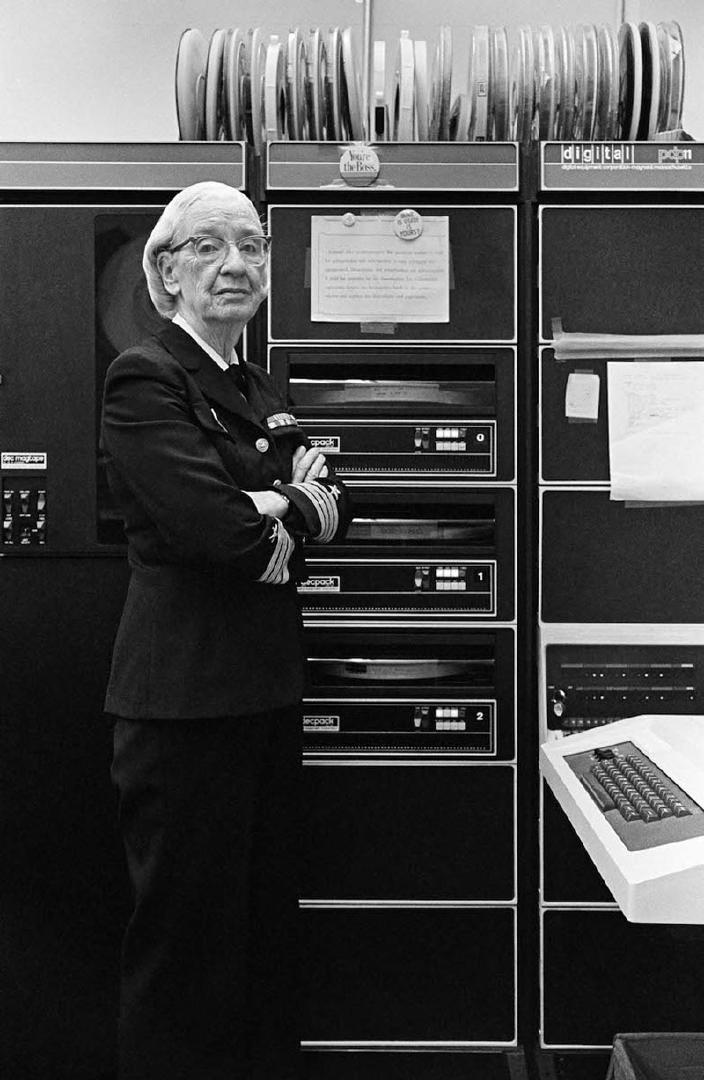

Grace Murray Hopper broke down gender barriers throughout her career in the emerging field of computer science.

Grace Murray Hopper broke down gender barriers throughout her career in the emerging field of computer science.

Ironically, her many accolades even included being named the first computer science ‘Man of the Year’ in 1969 by the Data Processing Management Association.

Born in 1906 in New York City, Grace Murray Hopper was raised when women were expected not to pursue careers. After the Great Depression, employed women were perceived as taking jobs from men, who were deemed to have a greater need to support their families.

However, Grace was raised in a family where education mattered. She attended Vassar College for her undergraduate degree in mathematics and physics. She completed her master’s and doctoral degrees in mathematics at Yale in 1930 and 1934 while continuing to teach at Vassar. Between 1934 and 1937, Yale awarded only seven doctorates in mathematics and only one to a woman, Murray.

Hopper, as she was then known (she married in 1930 and divorced in 1945 but kept her married name for the remainder of her life), taught until 1943, when she felt she should enlist in the military to support the war effort.

During World War I, women were accepted into the Navy as Yeomen, the first time women were allowed into the armed forces as anything but nurses. Navy enlistment was again opened to women in 1942 via the Women’s Auxiliary WAVES unit (Women Appointed for Voluntary Emergency Service). The Rear Admiral who presented the idea to the Senate stated they expected enlistment “will probably go up around 10,000 before we get through with it,” clearly not expecting the almost 100,000 women who served in the Navy before the end of World War II.

Hopper was accepted on her second enlistment attempt, and she graduated at the top of her WAVES class after a 60-day officer training. Gender bias was evident, however, as Hopper received a commission that read, “I do at this moment appoint him a Lieutenant (junior grade) of the U.S. Naval Reserve.”

When Hopper reported to the Navy Liaison Office at Harvard in 1944, she did not expect to be given only one week to comprehend the workings of the Mark 1 computer. Fortunately, Hopper’s lifelong interest in many disciplines and deep understanding of mathematics gave her the foundation to interpret groundbreaking technology quickly.

While working on the Mark II computer in 1947, Hopper and her team found a moth inside the machine's inner workings, which had prevented the relay from operating. Although they did not use the term ‘debugging’ to describe the incident at the time, this anecdote has been widely used to source the phrase. The remains of the moth are preserved safely inside the group’s log book at the Smithsonian Institution.

Hopper remained in the Naval Reserve after she entered the private sector in 1949 to work on the UNIVAC I commercial computer. Here, she began original work on a compiler system that would convert one programming language into another. FLOW-MATIC was developed for the UNIVAC system, and via the CODASYL (Committee on Data Systems Language) consortium, Hopper developed COBOL (Common Business-Oriented Language), which was adopted by the Department of Defense and standardized in the 1960s.

Although Hopper attempted to retire from the Naval Reserve as a Commander in 1966, she was recalled to active duty in 1967 and served as the director of the Navy Programming Languages Group as a Captain. Hopper retired a second time in 1971 but was recalled to active duty once again. She was promoted to Commodore, later renamed ‘Rear Admiral (Lower Half),’ making her one of few female admirals.

Hopper was passionate about collecting and filling three apartments in RiverHouse in Pentagon City with the objects she treasured throughout her extensive travels and career. Six years after her final retirement, Grace Murray Hopper died at her home in RiverHouse on New Year’s Day, 1992. She was buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors and posthumously received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2016, one of many military awards she received. Her other awards include the World War II Victory, Defense Distinguished Service, two National Defense Service medals, and three Armed Forced Reserve medals.

Her biographer, Kathleen Williams, describes her as having “an intense focus, a tireless dedication, and an irrepressible urge to innovate.” In addition to her many honorary degrees, titles, and accolades, the largest gathering for women in computing is named in her honor, with more than 15,000 women attending each year. Arlington County maintains a park on the grounds of RiverHouse in her honor.

Images