Holding the Line

The Arlington Line was never attacked but proved itself effective.

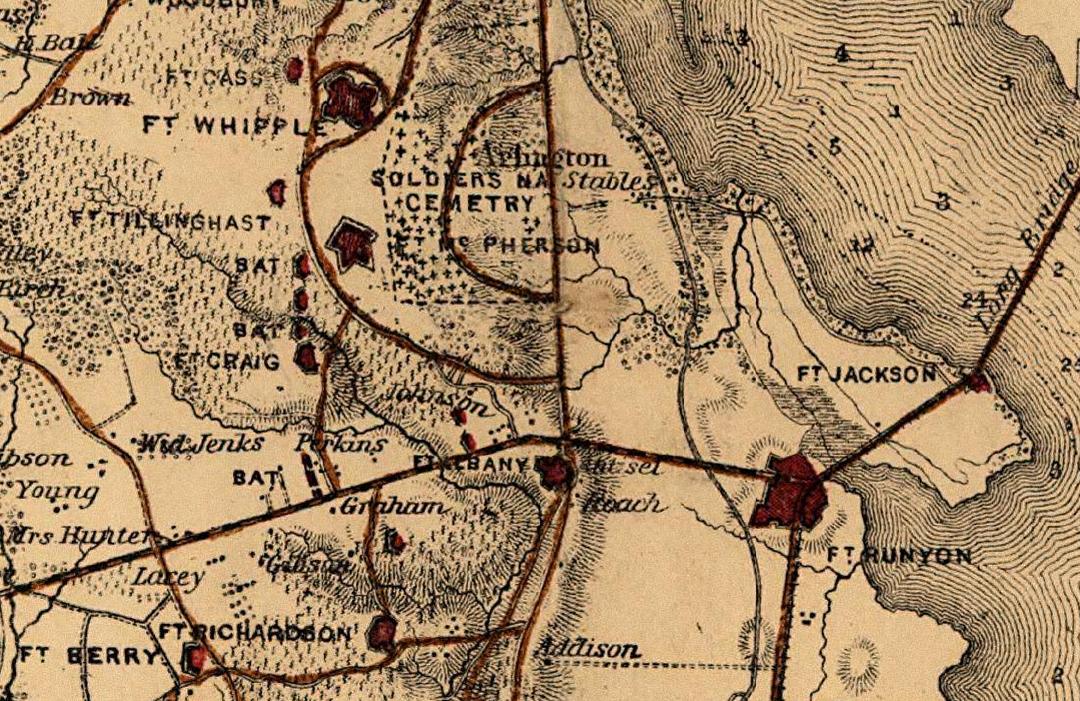

From 1861 until 1865, thousands of Union soldiers were stationed outside of Washington, building and guarding a ring of fortifications to protect the federal city. By the war's end, 68 enclosed earthen forts, 93 supporting batteries, and more than 35,000 yards of rifle trenches surrounded the District. That included 33 forts and 25 batteries south of the Potomac River.

When federal troops seized the Arlington Heights in May 1861, they immediately began the construction of Forts Runyon, Corcoran, Albany, and Scott to protect Washington. After the Union disaster at the First Battle of Manassas (Bull Run) in late July 1861, work was begun on Fort Ethan Allen, Fort Richardson, and a line of breastworks and lunettes called the Arlington Line.

A similar line of redoubts and breastworks covering the valley of Four Mile Run was more properly part of the defenses of the main base of the Army of the Potomac at Alexandria. The permanent garrison of these extensive fortifications within the present bounds of Arlington County, at least 10,000 men, greatly out-numbered the resident population, then some 1,400 men, women, and children.

The Arlington Line was never attacked but proved itself effective. This was evident after the Union's disastrous defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run in August 1862. Union troops had a secure perimeter defense to fall back on.

Major D.P. Woodbury was the Union engineer who designed and constructed the Arlington Line, and one of its forts, Fort Woodbury (which once stood in what is today Arlington's Courthouse neighborhood), was named for him. Initially, the Union Army began construction on a line of breastworks and lunettes (small crescent-shaped fortifications) west of the earlier fortifications. These and more extensive fortifications later constructed nearby also became part of the Arlington Line. They included a lunette (Fort Cass) and Fort Whipple, which became parts of Fort Myer and later renamed Joint Base Myer–Henderson Hall.

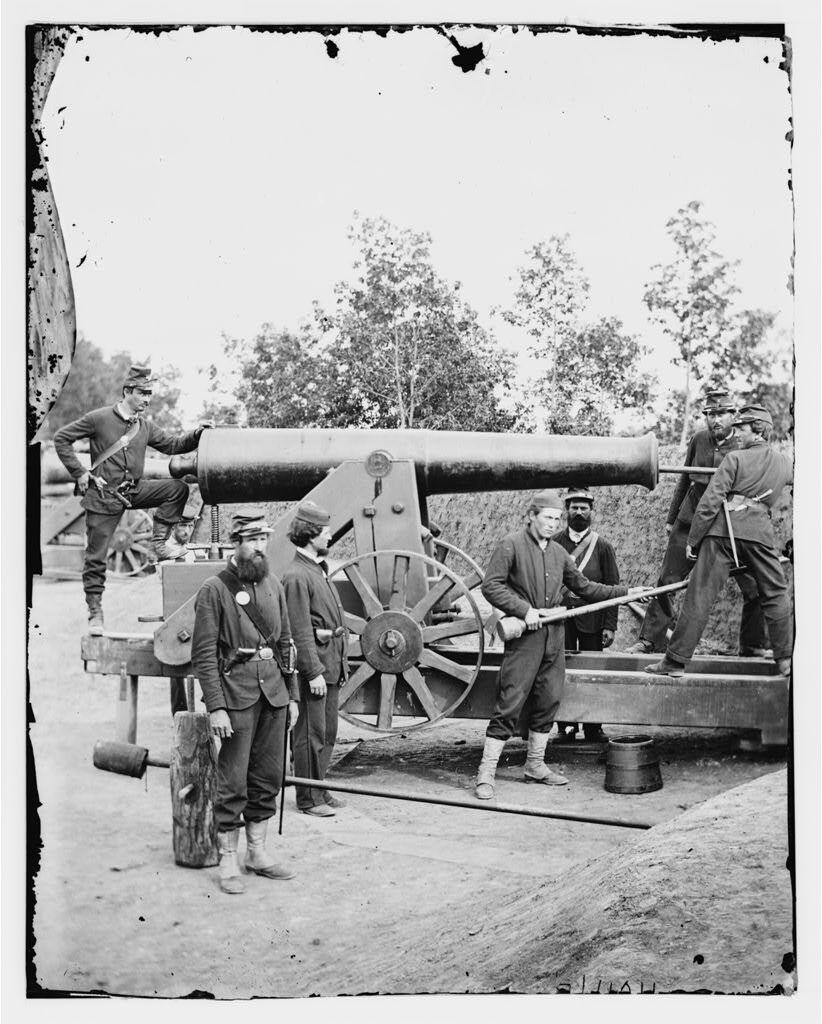

Nineteenth-century field fortifications or earthwork forts replaced stone or brick forts that were vulnerable to advances in artillery. Engineers used the topography of the location and constructed the fort primarily from earth and wood, materials readily at hand. Arlington Line forts were designed for temporary use.

Initially, soldiers were employed to build the forts, earth was removed from the "ditch" or dry moat surrounding the fort, and the earth was tamped (or rammed) into the framework. As the ditch grew deeper, the wall grew higher, extending to heights of 20-25 feet. The completed walls were 12-18 feet thick and were supported by a vertical pole system called "revetment."

As many as 10,000 men or more served in the forts at any given time, while nearby training camps prepared Union soldiers—including the Army of the Potomac—for battle. Arlington County (then called Alexandria County) was, in some respects, the largest military base in the world.

After the war ended and the troops went home, Arlington was returned to its farmers and small settlements. Trees began to grow again, and civilians who had fled came back. Jackson City maintained its status as a popular red-light district, although it was soon rivaled by a proliferation of brothels, taverns, and gambling halls in Rosslyn.

The forts, mostly made of earth and wood, fell apart. Some were stripped for building material, while others sunk slowly back into the ground under each year’s rain. Fort Whipple became Fort Myer in 1881 and is still active today, but a tide of 20th-century suburban development subsequently swept in, leaving only a few traces of the other remaining forts in the “Arlington Line.”

Many Arlingtonians today live on a spot where a fort once stood—where soldiers drilled in preparation for a Confederate attack that never came.

Images